Posted: April 28, 2015

If you haven’t already heard about Bonner Paddock’s tremendous story, we’re hoping to change that in more ways than one.

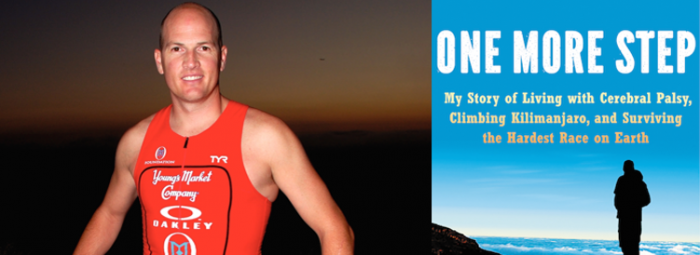

Bonner Paddock is an inspiring man who has accomplished amazing feats, including climbing Mount Kilimanjaro and earning the title of Kona Ironman. Born with Cerebral Palsy, his story is one that can inspire those with special needs and without! In honor of his recently published book, we will be giving away 10 free copies to our community ( please enter here – no purchase necessary!). To buy your own copy, visit his website (you really should!).

We asked Bonner to provide us a short overview of what early life with Cerebral Palsy meant for him and what the journey has meant to him as a result. We hope you enjoy!

—-

Pain was part of my nature, who I was, from the time I was born.

Early on in my life—well before my Cerebral Palsy diagnosis became the explanation for this this pain—I learned what to do with it. With no option to live my life without pain, I learned to put it away, to store it in some part of myself, so I could do, and be, in the world. My earliest memories centered around banging into things, tripping, and falling. Toes, fingers, wrists, arms, ankles, I broke them all, but there was no stopping me—and, indeed, nobody tried. That was not my family’s way.

As far as I can recall, my parents never said, “Be careful,” or “Bonner, you shouldn’t do that.” They knew something was wrong with me, but nothing was said about it to me for years. They treated me the same as they treated my two older brothers, and they expected the same out of me. At the heart of that treatment was tough love. No crying. No whimpering. No complaining. Get out there, try hard, make mistakes, take your lumps, learn from them, and try again.

My family might not have treated me differently, but I knew something was different about me. It was plainly obvious that I looked different and moved oddly. Wherever I went, my ankles flew wide, my knees touched, and my feet made this big slapping sound. There was no creeping up on anybody.

“Thumper!” the kids jeered as they heard me coming down the hallway.

Oh, yes. They called me that, and lots of other names besides, in school and at the playground. “DeCalf,” the kid without calves—that was one of the clever ones. The most obvious, “Boner” (instead of Bonner), was the most common. They would shout it while mimicking my gait, slapping their hands against the bottoms of their feet, making sure I could see.

The bullying was painful, like a punch in the gut during kickball. Many of those moments I have blocked out, just as I did the puzzled stares and under-the-breath comments from adults and children alike whenever I crossed the street. I could hear them thinking it, even if they were out of earshot: Something is different about that boy, but what is it?

It wasn’t until I was 29 that I began to come to terms with just what it was that made me different. Seventeen years earlier, I’d been diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy, but because I was often able to pass off my walk as an old sports injury, even those closest to me had no idea I had Cerebral Palsy. To most people, but most importantly to myself, I was simply living a “normal” life.

I finally began to share my story with people, not because of what I’d been through, but because of someone else, a four year old boy with CP named Jake. Jake, the son of a family I’d met through the Orange County chapter of UCP, had passed away in his sleep only a few hours after I’d first met him at the finish line of the OC Marathon and Half Marathon. His father had been running the marathon to raise awareness and money for CP, and the night after he finished, Jake passed away while he was sleeping.

Ever since Jake’s death, I’ve dedicated my life to redefining the limits of what is possible with CP. Jake’s short life and his enduring impact on those around him changed my perception of what it meant to be accepted and what it meant to be disabled. In the years that have followed, I set two world records, becoming the first person with CP to climb Mount Kilimanjaro and completing the Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii. I’ve also started my own nonprofit organization, the OM Foundation, to provide support to children around the world with disabilities. But it all started

Through these experiences, I pushed myself past the physical limits of what I thought was possible over and over again, but as I learned, the biggest limits were those that lived inside my head. The anger from my childhood, my frustration with my parents, the scarring from playground taunts—all of these were barriers holding me back from truly acknowledging my CP. It wasn’t until I could confront those issues, that I was actually able to accept my CP for what it is: the greatest gift that anyone has given me.

Climbing mountains and finishing races may seem like difficult challenges but they pale in comparison to what the families and children with CP do every day: look in the mirror and accept the role that CP plays in their lives. For years, I couldn’t do this, but thankfully, this limitation, like so many others, no longer holds me back.