Internal mini form

Contact Us Today

Once a parent hears the news that his or her child has Cerebral Palsy, life as they know it will change. But the adjustment to those changes sets the stage for acceptance of realities that are still infused with ambitious dreams and expectations for their child.

What dreams may come

When a child is born, it’s not only the beginning of a brand new life it’s also the culmination of hopes, dreams, and expectations. Parents naturally want to provide their children with a world of opportunity.

Those dreams run the gamut of hoping that a child turns out to be a thoughtful, generous person to loftier aspirations that occur to parents in the form of a question.

Will my daughter be the first doctor in our family? Is my son going to play college football?

Dreams flow through our minds before and after a child is born. Some are fleeting; others remain consistent throughout a child’s life. Most are born when we see our child take an interest in a sports figure, a student activity, or a neighborhood pasttime. And although some dreams may not on their surface be palatable, having them is always positive for both a parent and a child.

Wishes for a child are a vital underpinning to how a parent and a child relate to one another; dreams are always at work below the surface.

A diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy, for parents, can temporarily upend those dreams. Immediately after a diagnosis is received, parents are beset by an entirely different set of questions. What will my child’s life be like? How will they be treated? What does the future hold for my child, and our family?

Will my child go to college? Or have the ability to seek employment? Will he or she be able to live independently and some day have his or her own family?

There’s an odd thing about dreams. They can change based on circumstances, or they can remain stubbornly in place, unchanged by unforeseen barriers and obstacles that seem to stand in the way.

It is important that we note that there are children with Cerebral Palsy that pass, usually soon after birth or from an unexpected secondary condition such as pneumonia or seizure. The majority, though, live long and healthy lives with, of course, some form of physical impairment.

Parents are relieved to hear that people with Cerebral Palsy have run marathons, served in the military, tackled professions too numerous to be mentioned in this space, authored best-selling books, scaled mountains, performed on the Broadway stage, piloted airplanes, and directed movies. They’ve married, become parents, and lived secure, happy and long lives.

When a child has a disability, parents are initially so overwhelmed that it’s hard to see how their dreams for their child can remain intact. It can be easy to forget that a child – with or without a disability – is a unique personality with thoughts, ideas and traits that have yet to be discovered. His or her potential, like any other child, will unfold over time. And the exciting thing is that it’s okay to dream big because a child’s achievements are sight unseen – a parent cannot yet conceive of their significance.

Unexpected turns

A barrage of emotions ranging from sadness to guilt to anger to acceptance typically occur after a child is diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy. Suddenly, all of the hopes parents had for their child – everything they planned for their child – suddenly come into question.

Depending on a child’s condition, long talks, walks in the park, playing sports, bonding emotionally and having what is considered a “normal” parent-child relationship seems out of reach because frankly, it’s unclear if those things will ever happen. Parents of children with disabilities know that their child is often times struggling with basic tasks; seeing the big picture can be a challenge.

But once a parent is able to learn more about their child’s condition and bond with their child, new hopes and possibilities emerge. Hopes shift, and in some cases, dreams can remain the same. Albeit, adapted, modified or accommodated.

Today, parents have more tools in their arsenal than ever before. Adaptive and assistive technology make it possible for a parent and child to communicate their feelings even when the child is non-verbal. Specialized equipment has made mobility possible even for individuals with severe impairment or paralysis, like spastic quadriplegia.

A natural tendency for parents is to treat the unknown – in other words, what they will or will not be able to do – with fear. These feelings are quite understandable and are a normal part of the process parents go through.

There is, however, another way to look at these unknowns. Because a parent doesn’t know what the future holds, why not look at a child’s situation with optimism? Is it possible to consider that a child’s life may turn out to be better than expected? If the child expresses an interest, is there a way to explore their involvement? If a child likes a sport, is there an adaptive program that may fit his or her needs? If they like to draw but can only move their head, is there a head-stick option? If they would like to use the computer but can only move one foot, is a foot control available? If it hasn’t been discovered yet, is there a way to ask an engineer for guidance?

Instead of thinking a child may never speak in an understandable way, why not consider the fact that he or she may write a book using a computer? Or, instead of thinking that a child’s paralysis will keep him or her from playing in sports, why not consider that the day may come when he or she takes part in a wheelchair marathon?

All of these things have, and will continue to occur. All people, including those with disabilities, are capable of reaching heights that just may exceed a parent’s perception of their limits. A parent can benefit by resolving early on that their child will be a success, although their path may be laden with ingenuity and creativity. That tried and true adage comes to mind, “If there is a will, there is a way.”

The power of positive thinking

Parents may experience anxiety if they are asked by family members, friends, and educators to verbalize their hopes and expectations for their children. When it comes to discussing the topic with their child, parents may feel that expressing their hopes puts pressure on their child, so a dialog about what a child enjoys and what they want for their future may not occur.

Yet, children want to hear that their parents have aspirations for them; that they have boundless hopes for their future and confidence in their abilities. Children with disabilities, because of the challenges they face, have an intense need for their parents to acknowledge that they have options.

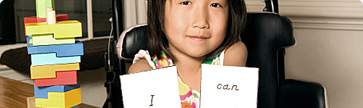

So much of raising a child should be focused on what they can do, as opposed to what they can’t. No child wants to feel as if their situation is hopeless, and if a parent doesn’t openly express their hopes and dreams for their child, that’s exactly the impression he or she may receive.

Conversation doesn’t have to be as specific as “I want you to play baseball.” The conversation can be as uncomplicated as “I’m bored, what do you want to do today. The sky is the limit!” or, “One day, you’re going to have so much fun at college.” Often a child’s interest develops through a parent’s own interest. If the parent likes to bake, children like to assist. If a father watches football, children like to be sitting side-by-side and cheering along with their father. If the family goes to the beach, the child likes to play in the water, too.

Always remember that the parents of the children that ultimately scaled mountains, served in the military, performed on the Broadway stage or penned best-selling books had the same fears as other parents of children with disabilities. At some point, the child harnessed hope, dared to dream, tried, and succeeded. The journey may not be steadfast, or without bumps, and let’s face it some of the things we try, go to the wayside. But, we try.

At some point, something came along that we succeeded at. Children, even with disability, are no different.

Dreams are attainable

Daring to dream that a child’s life may be better in the future than it is now is no easy task.

Some days, achievements that might seem marginal to other people are an enormous leap forward to a child with a disability and his or her parents.

These achievements should be celebrated. And, in an odd way, families touched by Cerebral Palsy who accomplish these strides together are bound by a genuine appreciation for life, and life’s simple gifts. A lesson some aren’t privy to.

Bigger achievements, the ones that are likely to open new doors and possibilities for a child take time. There are some things that parents can do to help their child reach higher.

The first is to let a child try new things, and to identify avenues they can take to pursue their interests. Let them work through their difficulties. If they have an interest, they may develop a way on their own. Support their efforts without first running to their rescue. Another goal should be to resist holding a child back – having a fulfilling life includes taking risks. Learning how to accomplish a task can be as much of a life lesson as succeeding, or failing.

A child’s inherent abilities and strength need not be impeded by a disability. The child is unique; he or she will reach goals and develop a skill set in a way that is different from anyone else.

Children with disabilities often have many achievements, and their parents should expect more successes, not fewer.

Inspirational Messages

A message can be verbal, or something that’s felt in the heart. What all messages have in common is that they can influence our perspectives for better or worse. Luckily, by gathering positive messages, the bad ones can be cast away.

- Accept Help

- Advocate

- Celebrate Your Child

- Dare to Dream

- Experience Magic

- Find and Foster Creativity

- Gain Perspective

- Get Your Mojo Back

- Keep the Family Together

- Let Go

- Listen

- Love without Barriers

- Pat Yourself on the Back

- Persist

- Plan Ahead

- Pursue Happiness

- Reinvent Normal

- Share Some Love

- Take a Break

- Welcome to Holland