Internal mini form

Contact Us Today

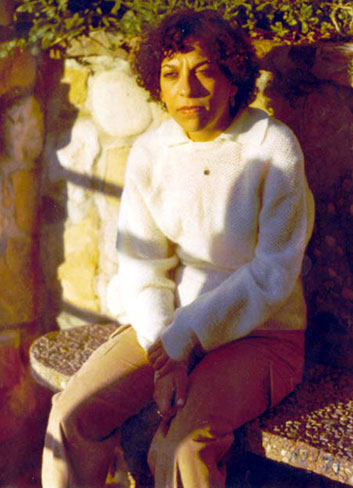

Stretching beyond boundaries

As a lifelong Californian, Karen Lynn Chlup wakes up each morning to a sunny day, and the first thing she considers is how to seize the opportunities of the day.

“I think many things in life have to do with your attitude,” said Karen, a 62-years-old resident of Torrance, Calif. “You think you can do anything you want to do; my motto is “You can do anything you put your mind towards doing.”

That motto is one that Karen has spent a lifetime living. Although she’s an in-demand fitness trainer that specializes in helping individuals with disabilities increase their level of physical fitness, Karen also won the right to better herself through higher education when she sued the State of California Department of Rehabilitation for the right to attend college. Hers was a case brought forth under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 that would open doors for people with disabilities to pursue higher education.

For Karen, the effort was one that would allow her to do all of the things that she desired to do at a time when people with disabilities enjoyed few legal protections, and attitudes were considerably less charitable than they are today.

“I knew that given the opportunity, I could learn and thrive in college,” said Karen. “I knew that I had those things inside myself.”

Growing up dancing

Karen Lynn was born March 9, 1951, the second daughter of Rubin and Kate Hershkowitz. She describes her childhood as happy and typical for a young person.

“I had wonderful parents. They made sure I had everything that I needed, and they made sure that I never felt like I couldn’t do something,” Karen said. “Growing up, I didn’t have the notion of what a handicap was. I was never left out of anything.”

Although the family was content, they were besieged with their share of heartbreaks.

Karen’s sister acquired rheumatoid arthritis from infected tonsils at 18-months-old, and after Kate took her in for a tonsillectomy, her physical issues were of little problem. Karen, however, wouldn’t be as lucky.

Karen, at the age of 5-months-old, fell into a ten-day coma and was paralyzed after receiving a DPT injection. Although she was given a 30 percent chance to live, Karen survived with complications. At the age of 18-months-old, Karen received a diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy with left-side hemiplegia. Although in the first grade she suspected she was having problems retaining information, she found ways in which to remember. In 1960, she was diagnosed with a learning disability.

“I wore a full length leg brace on my left leg,” she said. “My mother asked our doctor how I would ever learn to use my knees with that pad in place. She ended up removing the pad, and I learned to use my knees.”

Karen recalls there was nothing she would do or try while growing up and she attributes that to her mother who “did not treat me any differently than my eldest sister.”

Karen’s mother was a tireless advocate for her daughter’s health and well-being. Karen can remember week-after-week her mother, who did not drive, would carry her – with a purse and diaper bag dangling from one arm and Karen from the other – to a bus stop to ride to Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles for treatments and therapies.

School mates, however, were a little less compassionate, Karen recalls. She was a timid child who grew up in an era when there was less awareness of childhood disabilities and little provisions in the education system for children with impairment. She attended a school for children with disabilities at the age of 3-years-old and was told she would be held back if she didn’t socialize or talk to others in class.

Her mother found a neighborhood dance studio and thought Karen may like to learn to dance. It become her favorite activity. She took tap, ballet and jazz lessons that she considers to be the basis of her movement today.

“I had a wonderful dance teacher. His name was Al Gilbert, and he made dance fun for me. He made the dance steps into exercises,” Karen said, about the man who would teach her to hop, skip, jump, run and dance. “He believed in me and nurtured me.”

Karen’s first dance recital is still a vivid memory. “It was a very important day for me; not just because I was going to dance, but because I was going to dance with my teacher,” she recalled. “How mind-blowing an experience it was sharing the stage with [Al Gilbert] all alone. I felt like I had wings – I felt like I was no longer trapped in the body of mine.”

She also felt like a princess that day, dressed in a frilly and colorful costume.

“It made me feel beautiful and Al made me feel like a little princess,” she recalled. “Oh how I remember looking into his eyes; how empowered I felt.”

She soon learned to swim, hop-scotch, hide-and-go-seek, play Checkers, chest, tether ball, and more. Karen was told she could hang up her brace for good.

“The dancing was a big part of that,” she said. “Without the dancing, I don’t know if ever would have been able to do that.”

Challenges of youth

While Karen’s home life was going well, her life at school was another story altogether.

She had a learning disability called dyslexia. And on top of that, she attended a school that was exclusively for children with disabilities. At the time, it was called a “handicap school.” These schools typically had their own curriculum that typically fell well short of that offered through a conventional school curriculum; students were seldom prepared for the real world of work, and college was considered an impossibility.

“I went through 12 years of schooling and never really learned anything,” she said. “It was not the kind of education that I needed, and I knew it wouldn’t be enough for me.”

Also, Karen’s beloved father, Rubin, was diagnosed with a case of terminal cancer in the mid-1960s and died six months after her grandfather had passed. A few years later, a cousin was killed in the line of duty in Vietnam. Karen says the experience taught her to live each day and to love more.

After her graduation from school, she aspired to attend college. In 1968, Karen had her first appointment and experience with the California Department of Rehabilitation. The department gave Karen a battery of tests and determined that she was, to use the words provided in that era, “borderline mentally-retarded.” Karen, who had never been labeled, bravely moved forward in an environment that she felt sold her short.

“I was put into a work environment where I did nothing but fold boxes,” she said. “I knew I was capable of doing more. I knew that the label was not true.”

In her 20s, Karen attempted to enroll in college with the CDR’s assistance. Karen was told she didn’t meet the qualifications to pursue higher learning because she had not completed 12 units of coursework.

“I remember phone call after phone call, letter after letter, getting no-where,” she said.

Karen decided to seek legal representation and filed suit under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act against the CDR in 1976.

“I was told by my attorney that this was the first civil rights case of its kind. He said that either I would win the case and open doors for all people with disabilities, or I would lose and not be able to go to college,” Karen said. “I tried to stop the deprecating effects of being called “mentally retarded” and (of) not being given the same rights as a so called “normal person.”

Three years later in 1979, Karen won her case, and subsequently enrolled in Santa Monica College, Santa Monica, Calif. She went on to earn an Associates of Arts. She later held a professional career working in the recreation field. Karen also earned recognition for her writing; in 1983, she placed second in Kaleidoscope Literary Arts Magazine’s International Prose Fiction Art Contest.

Going through the lawsuit was a challenge, but Karen’s glad she asserted her rights.

“I knew that if I didn’t get my degree that I wouldn’t really get to the point where I needed to be,” she said. “I wanted to be independent; a high school education wasn’t going to be enough. I was driven to make something of myself and leave my learning disability behind.”

Life today

During Karen’s career in the recreation field, Karen earned several certificates, mainly in fitness training. An early devotee of chair aerobics and yoga, Karen became a self-employed instructor. Chair aerobics allows people with disabilities to exercise without having to stand for long periods of time.

Karen teaches classes at recreation centers and nursing homes, but also instructs clients one-on-one. She believes that fitness classes help people with disabilities in the same way dance helped her.

“I do both whatever my client needs,” she said. “I assess their needs, and we work out a program based on their abilities. I trained Parkinson’s patients back in 1987 at the Beverly Hills YMCA. The great thing about working with people is showing them that they can work out no matter what they’re situation is.”

Karen has been married to her husband, Christian, for 24 years, and has two stepchildren and two grandchildren, age 17 and 2.

Karen has also spent the majority of the last two decades lecturing and spreading the “I Can Attitude” to individuals with Cerebral Palsy and other learning disabilities.

“While they are part of my life, I spend my days writing articles for my blog,” said Karen, about the website she has maintained for 20 years. She is also finishing a novel to help others with disabilities.

Her advice to people with disabilities is to do whatever it takes to get an education and live independently. “The doctor told my mother there was a chance that I would be deaf, dumb and blind, and I guess I fooled them,” she said.

“I tell people that if someone tells you that you won’t be able to do something, do everything you can do to prove them wrong.”

For more information on Karen, visit her website:

As we grow and mature into adulthood we’re bound to have goals that may not seem to be attainable, or dreams we hope come true. While goals and dreams can be grandiose or simple depending on an individual’s personality and temperament, Cerebral Palsy is not an impediment to an exciting, and ultimately rewarding, life.

Adults with Cerebral Palsy

- Joe’l Ash – Overcoming Adversity

- Mike Berkson – Handicap This!

- Desaray Carroll – Receiving Recognition

- Rachel Chiapparine – Addressing Stereotypes

- Karen Lynn Chlup – Stretching Barriers

- Shevitta Collins – Accepting Outcomes

- Abbey Curran – Creating Confidence

- Robert Fayz – Funding Reductions

- Jon Gilroy – Transitioning to College

- Daniel Keplinger – Painting from Within

- Priscilla Morrison – Remembering Family

- Neil Sauter – Paying Forward