Internal mini form

Contact Us Today

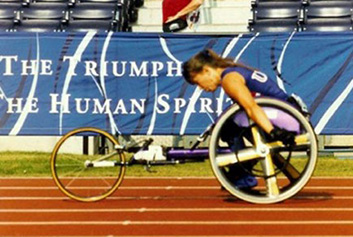

Wheelchair sports created confidence in Chicago athlete

Attorney, Athlete and Author

Linda Mastandrea overcame the effects of spastic diplegia – and her own skepticism – to become a record-breaking, two-time Paralympian, one of the most decorated paralympic athletes in U.S. history, and a practicing civil rights/disability attorney.

Growing up in Bolingbrook, Ill., Linda Mastandrea remembers doing everything with her twin sister, Laura. That is, except participating in gym class and participating in active recreational pursuits.

But fast forward several years, and the name on numerous medals, awards and athletic records is indeed Linda’s.

Linda, now 48 is a civil rights and disability attorney in the Windy City, says participating in wheelchair sports was the beginning of a journey that would transform a shy college student into a world-class track and field athlete. Also, athletics would give her the tools she needed to inspire others to aspire to new heights.

“When I was actively competing, I went from someone who was barely capable of wheeling a chair to someone who was breaking world records and winning medals,” said Linda. “It was something I never thought possible. Today, I am all about recreation.”

Growing up different

Linda and Laura were born in Chicago, to Robert and Dorothy Mastandrea. In a rare coincidence, the girls were the second set of twins in the family which included sister Donna and brother Bobby, who were 16 years older than Linda and Laura. She also has another brother, Tony.

When she was around two years old, Linda was diagnosed with spastic diplegia Cerebral Palsy. Despite her condition, she has complete use of her legs, and had what she considers to be a relatively normal childhood.

“Growing up, I walked and was carried around when I got tired,” she said. “I didn’t use a wheelchair until I started playing sports in college.”

In school, Linda excelled academically, but she placed limits on herself when it came to physical pursuits because she did not believe her condition was conducive to playing sports. Linda graduated in the top of her high school class and was accepted to the University of Illinois, where she would eventually earn a BA in speech communication.

It was at the university that Linda’s competitive fire was lit. In her freshman year, she met Brad Hedrick, the coach of the women’s wheelchair basketball team at the university, who encouraged her to join the wheelchair basketball team. Linda would ultimately spend three years on the team.

“What inspired me was the fact that I could play. I didn’t have to sit on the sidelines like I did growing up and watch everyone else.”

– Linda Mastandrea, U.S. Paralympian and disability attorney.

She also met track coach Marty Morse, who recruited her to join the university’s wheelchair track team, thereby paving the road for Linda’s participation in the Paralympics.

“Marty Morse helped me see I could succeed in that sport,” she said. “He saw me not just as an athlete but as a person, and believed in me wholeheartedly.”

But participating in wheelchair sports presented a unique obstacle for Linda, mainly because she did not use a wheelchair day-to-day. In the Paralympics, athletes of varying abilities will compete in categories in events in which they may use implements they may not use in everyday life; competitors with Cerebral Palsy often compete against one another.

“For me, the biggest challenge was learning to use the wheelchair, learning to handle the basketball, and learning to be part of the team,” she said. “All of it was a challenge. Practice is what changed it.”

But as she mastered basketball and track, a number of things began to change. She began to develop physical strength, but more importantly, athletics gave Linda confidence in a situation where she previously had none.

“It made me see myself in a whole new way,” she said. “I saw a whole new side of myself, and it rounded me out as a person.”

After she earned her bachelor’s degree, it could have been the end of Linda’s athletic career, but as it turned out, it was only the beginning.

As she began studying law at Chicago-Kent College of Law, Linda was inspired by what she was able to achieve in college athletics, and she also began training for the 1992 Paralympic Games that would take place in Barcelona, Spain. To compete in the 1992 games, Linda missed the first three weeks of the second semester; it’s a time she remembers as very busy.

Golden dreams

Linda was living in Virginia for work when she began entering road races and track meets. She was still being coached by Marty Morse (by mail), and returned to Chicago to join the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago’s track team, under the tutelage of Coach Norman Lange. It wasn’t long before Linda qualified for the nationals, and later, the U.S. Paralympic Team.

“That fall, I started law school and continued to train and raise money, since this was before the U.S. Olympic Committee funded Paralympic athletes,” she said. “So that year and through the summer, I trained, traveled, competed, went to school and studied, and that was my life.”

In September, Linda traveled to Barcelona, only to discover that all of her events were cancelled because they didn’t have enough female participants. But she didn’t give up. After graduating from law school in 1994, Linda competed in the World Championships in Berlin, Germany, where she won three gold medals and set two world records in the 200 and 400 meter races.

After taking the bar examination in 1995, Linda jumped back into training, and in 1996, she qualified for the U.S. team again, and would compete in Atlanta, Ga. This time, eight women were there to compete, and Linda took a silver medal in the 100 meter, followed by gold – and a world record – in the 200 meter sprint.

Linda considers her experiences at the Paralympics a highlight of her life.

“It was the most exciting thing I’ve ever done,” she said. “It’s just overwhelming the feelings that you have crossing that line in front of everyone else, and sitting on the medal stand, and seeing your flag and hearing your anthem.”

In addition to the Paralympics, Linda competed for her country in three world championship events as well as the Pan American Games and the Stoke-Mandeville Wheelchair Games, winning 15 gold and silver medals in wheelchair track collectively.

Athletics and beyond

Linda’s experiences as a Paralympian gave her valuable insight into what disabled people are capable of, and informed her decision to help other disabled individuals in her law practice. Today, she is the principal of a law firm that focuses on disability law, civil rights, and helping people who have found themselves the victims of discrimination in terms of employment, education, housing, and government services.

But Linda is more than an attorney; she has been an advocate for the disabled, speaking several times a year about the nature of disability and what it means – and does not mean – to have a disability.

“I think the time for tokenism is long past. I think that people with disabilities are interwoven into the fabric of our community. They are–I am–part of society, part of the community,” she said. “It is not an ‘us’ and ‘them,’ it is a ‘we.’ How are ‘we’ going to work together to ensure that people have access to the products and services they need?”

Linda reminds us that simple concepts such as being a consumer and “being able to get to what you need in the way that you need, to live the way you want to live” should be as easy for the person with disabilities as it is for the able-bodied. Everyday journeys to work, having dinner with friends, going to the movies, pumping gas and living independently in a safe, warm comfortable place are not yet universally available, but could be if we all come together and make it happen.

Its Linda’s hope that the lessons and lectures she takes part in helps able-bodied people better understand people with disabilities, and people with disabilities understand barriers that society places on them as well as the barriers that people place on themselves. Also, Linda lectures about the importance of including the disabled people in the labor force so they can further build their skills and talent.

In 2006 she collaborated with her sister, Donna, on a book titled “Sport and the Physically Challenged: An Encyclopedia of People, Events and Organizations.”

On the athletic field, she has been the recipient of several honors, including being named the Disabled Athlete of the Year by the International Olympic Committee in 1996. Linda was also inducted into the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in 2010, and was named an Outstanding Woman in Sports by the YWCA of DuPage, Ill., in 1995.

Additionally, Linda serves on several boards, including the Variety International Paralympic Committee Legal and Ethics Committee. She also spearheaded the effort to bring the 2016 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games to the City of Chicago, where she made her case alongside President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley. Ultimately, however, the 2016 games were awarded to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Today, Linda lives in a two-bedroom condominium in Chicago with her husband, Jesse Rodriguez, and two cats. When she was competing, she discovered that using the wheelchair was easier for a busy professional, and although she walks short distances, she uses her wheelchair almost exclusively outside the home.

She said several factors have made a difference in her life, not the least of which is athletics.

“What inspired me was the fact that I could play, I didn’t have to sit on the sidelines like I did growing up and watch everyone else,” she said. “Sports made me a whole person, made me believe in myself in a way I never did. It made me believe I had the potential to be and to do anything.”

The other important factor is her family.

“A lot of it was my upbringing and family support, my parents, my brothers and sisters, especially my twin Laura, because we spent so much of our lives together,” she said. Linda also gave credit to her coaches who believed in her even when she could not believe in herself.

Her advice to would-be athletes with disability is to set their inhibitions about sports aside.

“Initially I myself was skeptical about my ability to play, so I was my own worst enemy as far as that goes,” she said. “There are sports and adaptations for everyone, no matter what physical limitations you might have.

“Life is short,” she added. “Make the most of every opportunity that comes your way.”

Athletes with Cerebral Palsy

Athletes are mythic figures that have used their bodies to achieve an enviable level of fitness. Although most people don’t associate individuals with Cerebral Palsy with sports and other acts of endurance, these athletes use their bodies to achieve feats of physicality that are only surpassed by personal satisfaction and confidence.

- Sam Broughton – Martial Arts

- Drew Dees – Shot Put

- James “Rooster” Gallion – Parkour

- Dick and Rick Hoyt – Triathletes

- Benjamin Jackson – High School Sports

- Cody and Cayden Long – Triathletes

- Linda Mastandrea – Paralympian

- Ryan McGraw – Yoga

- Kyle and Brent Pease – Triathletes

- John Quinn – Navy

- Jack Runser – Wrestler and Bodybuilder

- Jerry Traylor – Mountain Climber

- Marty Turcios – Golfer

- Ahkeel Whitehead – Paralympic Hopeful

- Duncan Wyeth – Paralympian